IRISH RENAISSANCE by Allen Harbinson

This evening, as I sat in front of my computer in a renovated farmhouse in West Cork, feeling miserable because I recently trashed my car and had to cancel my two ferry trips back to Paris, I was suddenly uplifted to hear on the radio that Ken Loach has, after many undeserved rejections, won the prestigious Palme d’Or at this years Cannes Film Festival.

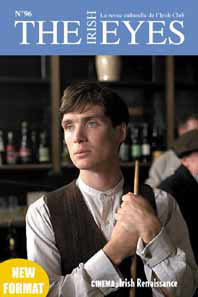

I wasnt uplifted because Loach is a fellow Irishman (for he is, indeed, a born and bred Englishman) but because he has made a lot of deeply committed social or political movies and should have had the prize before now. I was, however, also uplifted because the movie in question, The Wind That Shakes the Barley, was backed in part by the Irish Film Board and is the dramatised story of the Irish war for independence. Set in 1919, it tells the tale of two brothers, Damian and Teddy, who become involved in their separate ways in that conflict and end up, as so many brothers of the time did, pitted against each other. That one of those brothers is played by Cillian Murphy made me dwell on the fact that the Irish film industry is suddenly having a renaissance, with new movies forthcoming from highly talented directors (John Boormans The Tigers Tail, David Gleesons The Front Line, Paddy Breathnachs Shrooms), and that at least three Irish actors, including Cillian Murphy, are being viewed as the hottest young thespians around even in Hollywood.

Cillian Murphy is, of course, one of them. Born in Douglas, Cork, in 1976, he gained his first minor role in Quando (1997), had a sound training in a variety of forgettable TV productions and small-budget movies, inched into the big time with minor roles in The Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003), Cold Mountain (2003), Batman Begins (2005) and Red Eye (2005), then hit the big time with his stunning performance as the hopelessly innocent transvestite in Neil Jordans wonderful Breakfast on Pluto (2005). An actor who remains, in a sense, unrecognisable to the average audience, because he changes his appearance like a chameleon changes its skin, he will next be seen in Danny Boyles Sunshine, billed as a sci-fi thriller. While this seems a dubious choice for an actor of Murphys acute sensitivity, who knows what he and Boyle will make of it?

Whether or not Sunshine succeeds in advancing Murphys career, it is highly unlikely to stop it, given the breadth of his talent. Nor is a single failure likely to stop the extraordinary advance of another Irish actor, Jonathan Rhys Meyers (born in Dublin, 1977, but raised in Cork), who, though hugely talented himself, has stated modestly that he thinks Murphy is the best of the best. In truth, its a toss between the two, though for my part, Meyers comes out front for the sheer fecundity of his career to date. Like Murphy, he is a chameleon of different personas, but his diversity seems even greater, ranging from his modest beginnings in the likes of Michael Collins (1996) and The Disappearance of Finbar (1996) to his real break-

out in Velvet Goldmine (1998) and the hugely successful Bend it Like Beckham (2002), then on to his Golden Globe Award-winning Elvis the Early Years (2005), his recent co-starring role (with Scarlett Johansson) in Woody Allens Match Point (2006), and his supporting role in the recent Tom Cruise box-office smash, Mission: Impossible III. At the very least, this shows remarkable diversity.

It may be no accident that Meyers has work-ed twice with another of his heroes, the third in our trio of rapidly ascending Irish actors: Colin Farrell. Undeniably the most popular of the three, if not the most talented, Farrell, born in Castleknock, Dublin, in 1976, has ascended like a rocket in the past few years through his roles in mostly Hollywood blockbusters, including the likes of Tigerland (2000), Minority Report (2002), Phone Booth (2002) and, more notoriously, Oliver Stones Alexander (2004). Coincidentally, Farrell and Meyers both inched into their careers with minor parts in The Disappearance of Finbar and both appeared in Alexander, with the former taking the lead role. But it may be indicative of the difference between the two Farrell as the matinee-idol, Hollywood-driven, personality actor and Meyers as the individualistic, artistically motivated talent that Farrell will next be seen in Michael Manns big-budget Miami Vice while Meyers has chosen to return to his roots with the more modestly budgeted August Rush.

The story of a charismatic young Irish guitarist (Meyers) and a sheltered young cellist (Keri Russell) who meet in New York, fall instantly in love, but then are torn apart, leaving an orphaned child in their wake, August Rush has been directed by Kirsten Sheridan, daughter of the esteemed Irish director, Jim Sheridan (interviewed some time back by The Eyes). If the daughter turns out to be as talented as her father, the movie should be something well worth watching – certainly with Jonathan Rhys-Meyers in the lead.

An Irish renaissance? In commercial as well as artistic terms, it certainly seems so. Lets roll out the red carpet.

www.thewindthatshakesthebarley.co.uk

SAMUEL BECKETT, THE FRENCH CONNECTION PART 2:

by Declan McCavana

In the second section of this two-part series on Samuel Beckett to mark the centenary of his birth, The Irish Eyes looks more closely at how the writers work is examined and dealt with differently through Anglophone and Francophone eyes.

After settling in Paris in the late 1930s and befriending James Joyce, Beckett chose to write mainly in French in order to free himself from the apparent tyranny of his too-poetic English style or as he put it himself, in order to cut away the excess, to strip away the colour. Some critics, however, maintain that his use of French was an attempt to distance himself from his master Joyce. Whatever the reason, Becketts choice to write in a language which was not his mother tongue lends to the French versions of his work, a timeless and placeless nature which, to some extent, is less the case in the English translations, all of which he insisted in carrying out himself. Quite clearly, in his auto-translations, Beckett allows his underlying Irishness to come more to the fore, through the vocabulary and turns of phrase used. As Barry Mc Govern, considered by many to be one of the most versatile Beckettian actors of his generation, puts it, talking about the author of Waiting for Godot: There is a particular Irishness we feel, a Hiberno-English sense of syntax and cadence. We have a nationalistic claim on him in some way, and not a bad way.

Yet, Beckett is also cherished, it might even be said, revered, in the country of his adoption. After all, it was in France that he decided to settle, it was in Paris that he did practically all his later writing and it was on the Parisian stage that his major dramatic works were to be first presented to the world. En Attendant Godot, was first produced on January 5, 1953, in the Left Bank Théâtre de Babylon in Paris. The play’s reputation in France was made almost immediately with very favorable reviews and positive audience reactions. According to Godots first director, Roger Blin, the critics came and the play was reasonably well understood. Thats how it works in Paris, by word of mouth. On the contrary, Godot was greeted in a much more circumspect way by the Anglophone world. Beckett translated the work himself and it premiered to mixed reviews and dubious audience reactions in London in 1955. However, after Beckett was explained by certain well-known reviewers, notably Kenneth Tynan and Harold Hobson, the London audiences warmed to it and the plays fame and success gradually spread.

This original difference in appreciation by Anglophone and Francophone audiences was later to be mirrored in the emphasis placed upon different aspects of Becketts dramatic work by English-speaking and French-speaking directors. The latter have a tendency to seek out and emphasize the more philosophical elements in the plays, paying enormous respect to le texte and keeping very close to the original stage directions, whilst the former play more with the humour and the dramatic possibilities offered by incongruous situations (at times to the irritation of Becketts copyright holders, his estate, who often insist on no liberties being taken with the original).

Beckett himself would have appreciated both styles, having after all translated the works himself and thus provided the English versions with their Hibernian slap-stick touch and yet at the same time being notoriously insistent on having the scenes played exactly as he saw them. At one stage, writing to Roger Blin, he asked him to just be kind enough to restore it (a particular movement in Godot) as it is indicated in the text.

Whatever our reactions to Becketts works as Francophones or Anglophones, French or Irish, Beckett, like his friend and erstwhile tutor Joyce, represents a bridge between English and French-speaking culture and symbolizes like very few others the Irish French Connection.

Stop waiting

Beckett Remembering, Remembering Beckett Edited by James & Elisabeth Knowlson

www.bloomsbury.com

If you think you have read everything about Beckett, James Knowlson, the authorised biographer, and his wife Elisabeth, offer us in an amusing manner, a dialogue between Beckett and his parents, his friends and people he knew. It is a biography of many witnesses, and the memories differ according to who is remembering, whether it is Beckett himself or those who surrounded him.

A well written book, it reflects the Knowlsons affinity with Beckett, but I must admit I prefer to submerge myself in Sams texts. At the beginning of the 21st century, Murphy, Molloy and The Lost One strike a true note. G.S.

www.tcd.ie – www.ucd.ie

RUBBER DUCKS by Louise Cunningham

After a winter that seemed to go on forever, and a May so cold it could have been November, summer suddenly burst upon us for the bank holiday on the first weekend of June, as skies cleared and temperatures shot up to give us the long week-end of our dreams. And just in time, too, for the launch of the 3-day-long Maritime Festival in Dublins Docklands.

Once a wasteland of warehouses and empty lots, this area only came to most peoples notice with the opening of the Point Depot, as they crossed through it probably for the first time ever on the way to a concert. Office blocks and the odd hotel went up but for years the docklands had a soulless, deserted quality. Not any more, as the area stretching east of O’Connell Bridge along the quays of the Liffey is now the site of the largest urban regeneration project ever seen in this country. A huge development of apartments, restaurants, theatres, and Irelands first National Conference Centre, will mean the transformation of the Docklands into the epitome of modern aspirational living. Some residences and businesses are already open, and very nice it looks too (as long as you aspire to spend your time in the gym or Marks and Spencer). With the injection of a little variety it could become a very attractive new quarter.

The festival, brainchild of the Docklands Development Authority and winner of an Irish Times 2005 living Dublin Award, is designed to draw people into the heart of this huge project. As we entered an unfamiliar part of town in unfamiliar sunshine, the first sight was the tall ships moored along the north quays. They made a magnificent backdrop for the action that stretched all the way down to the Point, with two music stages, street theatre, art and plant sales and an array of food stalls offering everything from South African barbecue to chocolate-dipped strawberries. Even the River Liffey looked cute, strewn with the remains of Saturday’s world record-breaking charity duck race: the world’s largest, with 150,000 rubber ducks, weighing two and a half tonnes. Of those launched, 132,000 made it down the one mile course over a period of 3 hours… but that leaves a lot behind and the little blighters were popping up for days afterwards. Boats on the river were scooping up strays and lobbing them to the crowds, which will explain why everyone you visit in Dublin from now on will have a rubber duck in their bathroom.

Call me disloyal, but it didnt feel like Dublin at all. Contrary to some public entertainments, there was no sense of enforced jollity, of pretending it was more interesting than it really was. More strikingly, for an outdoor summer event in this country, where were all the drunk people? Out of around 100 stalls, only one was for beer, is the answer. With stiltwalkers, magicians and entertainers making every-one laugh, we were all content to spend the day strolling and smiling, watching free entertainment or shopping for a painting, an ostrich burger or a Japanese willow tree.

With 55,000 attending it was about pleasure on a large scale; it says it all, really, that the Jeanie Johnston, a replica of the famine ship that carried Irelands starving to America, is doing pleasure cruises on Dublin Bay. But we were due our day in the sun, and behaved ourselves so well that perhaps weve earned a few more. More disloyal thoughts as I watched the camper vans coming off the car ferry: Will they get the wrong impression? Will they think that Dublin is always full of smiling people dancing in the sunshine?

Heres hoping. The summer fun continues in Temple Bar throughout July and August with the annual Diversions Festival. Yet more free stuff for our entertainment and this year it’s been expanded. Highlights include a circus festival, with acrobats and jugglers from as far afield as Canada and Tanzania, and a street theatre trail featuring plays by local authors performed in the streets and doorways of Temple Bar. There is also the usual open-air cinema (classics, short films and blockbusters) and, if henna tattoos are your thing, the Moroccan market returns for its second year. I could get used to this.

www.docklands.ie

TOP

JOHN SPILLANE AT THE CENTER OF THE UNIVERSE

by Mick Walsh

I have a Cork superiority complex; for me its the centre of the universe. My songwriting style is about keeping it real and from the beginning Ive almost unwittingly wrote songs about Cork, the place I know best.

John Spillane is fast becoming a local hero. At the launch of Cork as European City of Culture in January 2005 he performed the specially commissioned Farranree on Patrick Street in front of upwards on 100,000 people. Last April I sold out the Cork Opera House and got three standing ovations; it was a massively exciting night and a huge well of support.

Spillanes musical odyssey has taken him from the celebrated Stargazers to his globe-trotting adventures as singer with Trad favourites, Nomos. In 1997 he embarked on his burgeoning solo career with a striking debut album The Wells of The World. Since then he has developed a darker, madder side. Its true Ive become saucier and braver as Ive developed a solo performance. Having to take centre stage and take the bull by the horns, Ive written a few darker songs such as The Mad Woman of Cork. With Nomos I was only doing the odd song and playing jigs and reels, whereas my solo career includes a much broader range.

In 2005 his latest album Hey Dreamer, released on EMI, enjoyed commercial success going to number four in the Irish charts, with the single The Dunnes Stores Girl rising to number six. A lot of people got a kick out of the song, written for a dare about a girl who worked down at Dunnes in Douglas.

In 2003 his musical genius was rewarded with a Meteor award and he added the second gong in 2006 for Best Folk/Trad; needless to say I beat off competition from The Chieftains, Altan and Sinéad O’Connor!

John is part of the unique Gaelic Hit Factory, a songwriting partnership founded with childhood friend Louis de Paor. Louis has become a major figure in Irish language poetry and weve now started recording a double album in Irish. Its a concept type with songs and spoken poetry in Gaelic and English.

Spillanes song cover a broad church, from the arrival of Orca the Killer Whale in the River Lee to waltzing in the aisles with a Dunnes Stores girl. They have been recorded by a myriad of Irish artists, from Christy Moore to Karan Casey and Sean Keane; that gives me great pleasure. So what is the unique approach which underpins his compositional success? I carry around my songs in a diary, which Ive been writing for the past 30 years, and Im currently up to 134 songs. I aim to write one song a month although Ive not yet written any this year. Im the tortoise and steady wins the race. I continue to write songs in my style, and maybe the killer hit song will emerge, but theres nothing I can do to force that.

John Spillane is a wonderful singer songwriter,a significant artist who has something to say and says it with commitment, style and authority. Vocally, he is quite unique with an almost Sean-nós element, a voice full of honesty, commitment and sensitivity. His compositions from Johnny Dont Go to Ballincollig to The Moon Going Home have been described as highly original in concept, full of imagery and wonder and tasteful, visionary songs from a gentle, insightful spirit. As a live performer he is totally engaging, a true poet who wraps his poetry in memorable melody and gently guides audiences through the vastness of his understated gems.

Late bloomer or tortoise, John Spillanes musical offering is a rich broth of beautiful lyrics and melodies carefully distilled in the pressure cooker of performance; the result is the musical equivalent of the pure drop.

www.johnspillane.ie

DOCTOR JOHN DE COURCY, FRANCOPHILE IRELAND SAILS ON

by RJ Doyle

On 3 June a memorial service was held for Doctor John de Courcy Ireland in Monkstown Church, Dublin. He died on 4 April, aged 94. High-level political and naval representatives attended from France, China, Britain and Ireland. Doc Irelands passing had already sparked a flood of writing and broad-casting about this truly remarkable man, his achievements and how he inspired almost everyone he met.

How to sum up such a full life in a short article? Rather than start with the sea, as most writers do, lets begin with France. Sure enough, the French have always embraced the sea and listened to Doc as they would his good friend, Jacques Cousteau.

Doc was a great traveller, loved many countries and mastered many languages, as he joked, to converse with the lovely mermaids in all those ports I visited ». Though raised in Ireland by his grandmother, he was educated in England. He won a scholarship to Oxford at 17, but ran away on a Dutch cargo ship bound for Argentina instead.

He was born in India. His father, a British army major, had been assassinated in Beijing in 1914 and his mother remarried there. He stayed in close contact with China, promoted relations between the two countries and was awarded the Ambassador of Friendship in 2002. Fittingly, Chinese ambassador Zhang Xinsen attended the June memorial.

But with Huguenot blood coursing his veins, Doc loved France most of all, for its history, culture and, yes, that différence. What would we do without the French he would boom as the foreign media decried yet another strike or singular political manoeuvre from Paris. And France loved Doc back, feting him with honours, including from the prestigious Académie de la Marine. As French ambassador to Ireland, Frédéric Grasset, put it to me at the memorial service, I have come not just out of duty, but

friendship and my own love of the sea.

Several other governments honoured Doc as well – Argentina, Portugal, Spain, the UK and Yugoslavia. But until his death, the Irish government was deafeningly silent about his work, despite his contribution to the Maritime Institute and museum, the lifeboat, and tireless work to improve working conditions at sea and promote the countrys marine heritage.

Doc had already had a full life when I first met him at Newpark School in 1980. He thrived from teaching, and it was now his job, already approaching 70, to give this disparate gaggle of pupils a final leg-up into university, or rather as it turned out, the world. For most of us, he succeeded, and became a good friend too. He would listen, learn, teach and motivate, what Brazilian writer Paolo Freire would describe as the ideal teacher-student.

Doc was also a well-known political activist and anti-sectarian nationalist who campaigned hard for social justice, often with his wife Betty (late 1999) whom he married in 1937. However, his innate fairness, intellectual independence and determined honesty left him isolated and vulnerable to some farcical mistreatment, as beautifully illustrated when he was sidelined by the Labour Party in the 1940s red alert, partly on suspicion of his unusual name, only to be later expelled from the Communist party for his anti-Soviet views.

The sea was Docs destiny. He loved its mystical character, as reflected in his favourite song, Jean Ferrats Raconte-moi la mer, which he popped on for us at school. Walk with him along the Vico Road and he would soon gaze out over the bay and become lost in memories of people, encounters, countries. He respected the seas immense power, and its unforgiving response to a sloppy ships command, the true reason behind his linguistic mastery.

Doc loved conversation and debate. In 1982 he hosted a programme on RTE radio about his life. I was among the guests. Why had Ireland, an island, virtually turned its back on the sea? Doc asked. Even landlocked Switzerlands merchant navy was bigger. How many Dublin restaurants faced the sea? One, a hotel bar almost perched over his local Dalkey Sound, has since been demolished.

Could it be that fish was our penance? ventured a guest. Jim Kemmy, a leftwing politician from Limerick, saw it simpler: he, like many compatriots, came from Terra Ferma. And the Ferma (firmer) it is, the less the Terra (terror).

Doc was a fit man. Once when he was already well over 70, I remember him bounding ahead of me as we ran for his train in Paris-St Lazare, suitcase in hand. But what really keeps a person going is mental alertness: Doc read and wrote prolifically, and always kept up correspondence. He never complained about growing old, except after an occasional blindness attack. But the scourge of age eventually bit into his mind, particularly after he was taken into care. Doc was a free spirit, and despite very kind staff, he felt as though in an oubliette, far from his beloved pale marine dawns. He lasted nearly two years. In a rare lucid moment towards the end, he sighed, « sometimes you wonder what it’s all about. You really do. »

One evening, Doc dozed off, with his daughter by his side. This is it, she thought, when suddenly he roused and started to whisper to her, in French. It was one of their last conversations. Two days later Doc finally fell asleep for good.

Books by John de Courcy Ireland include The History of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, The Admiral from Mayo, Ireland’s Sea Fisheries, and Ireland and the Irish in Maritime History. He also completed a to-be-published autobiography.

www.ucd.ie